Words: Heritage Railway/Brian Sharpe

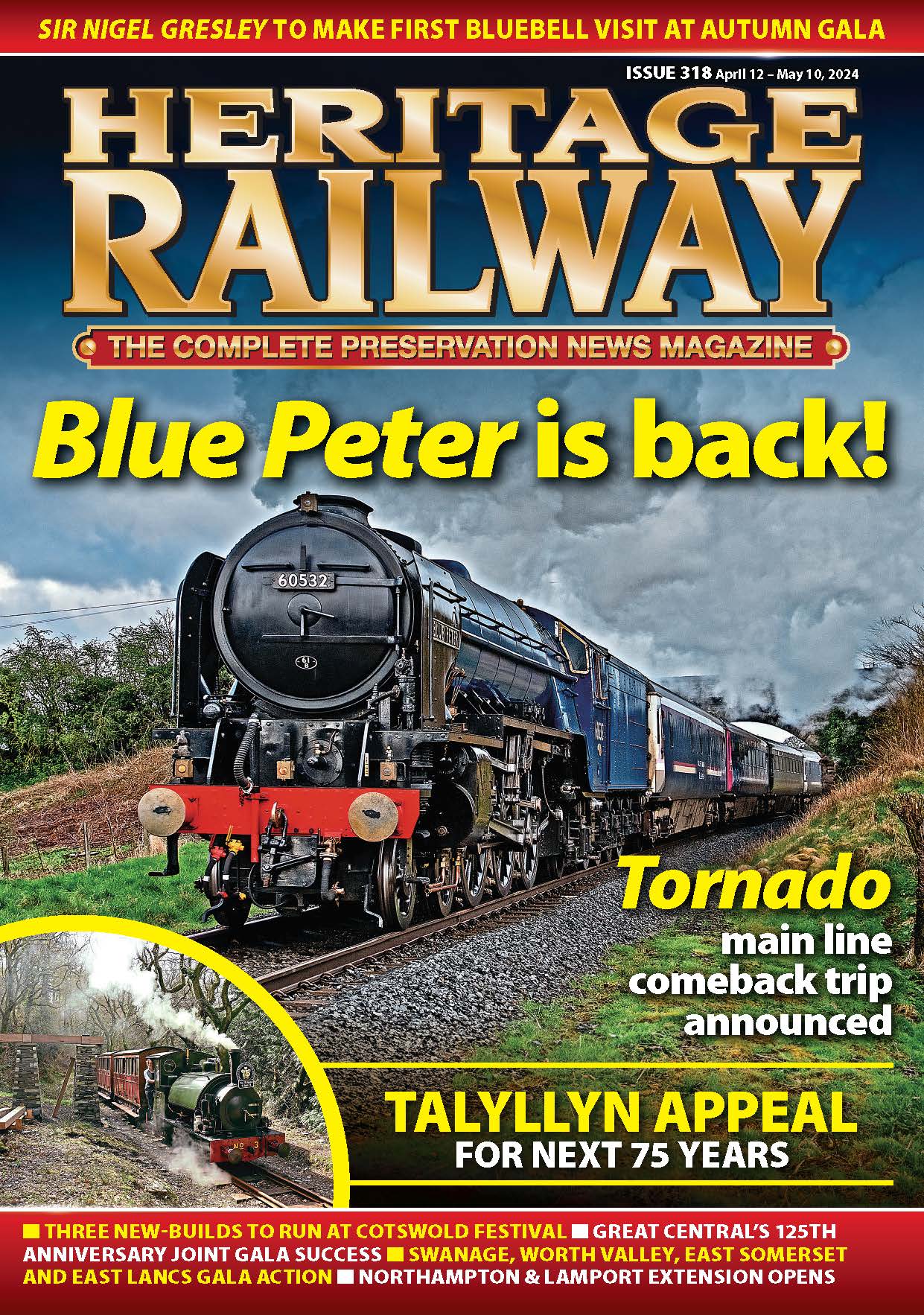

Which are Britain’s top 10 steam engines? Brian Sharpe compares the history and performance of the 10 biggest working main line engines in roughly chronological order of the introduction of the class.

Britain’s elite working steam locomotives are those registered to operate main line trains on the Network Rail system. In recent years, there have been fewer of the smaller engines and the heavier main line railtours have been in the hands of a select few Class 7 and 8 express steam locomotives.

In addition there are a number of Class 5 and 6 4-6-0s that generally haul lighter trains, often on secondary routes such as the West Highland extension, most subject to an overall maximum of 60mph as dictated by somewhat smaller driving wheels.

The system of power classification was devised by the London Midland & Scottish Railway as a development of a system first instigated by the Midland Railway. The smallest shunting engines on the LMS were classified ‘0’ and the largest Pacifics were Class ‘7’. The Stanier 2-8-0s were as powerful as the largest Pacifics and were given the power classification ‘7F’. Engines could be classified ‘7P’ or ‘7F’ for example if they were designed for exclusively passenger or freight work, while those that were suitable for both were simply Class ‘5’ for example.

Enjoy more Heritage Railway reading in the four-weekly magazine.

Click here to subscribe & save.

Confusion crept in to the system with the LMS Jubilee 4-6-0s, which were more powerful than a Class ‘5’ but not quite a Class ‘6’, so the LMS designated them ‘5XP’, effectively ‘51/2P’. This anomaly was removed by British Railways after Nationalisation by making Class 7s into Class 8s, Class 6s into Class 7s and 5XPs into Class 6s. The system was applied to the other BR regions but was adopted with varying degrees of enthusiasm.

The concept of mixed traffic locomotives is relatively new and the classifications ‘5MT’ or in some cases ‘6P/5F’ became more widely used in BR days but very inconsistently and the London Midland Region continued to refer to a ‘5MT’ as simply a Class ‘5’.

At the present time there are 10 express steam locomotives of class 7 and above certified for main line use and currently in working order, although there are several more under repair, restoration or overhaul and expected to enter service in the near future. These 10 serviceable engines form a remarkably comprehensive cross-section of the history of British steam locomotive development over the period from 1923 to 1951, and enthusiasts are still keen to compare the performances of these engines, carrying out the duties they were designed for.

LNER A3 No. 60103 Flying Scotsman

Flying Scotsman is now the oldest steam engine still active on Britain’s main lines and the only preserved non-streamlined Gresley Pacific, but has many other claims to fame.

Britain’s first Pacific was the Great Western Railway’s The Great Bear, designed by George Jackson Churchward in 1908, but no more were built and it was not until 1922 that Sir Vincent Raven built some Pacifics for the North Eastern Railway, while Nigel Gresley built some for the Great Northern Railway.

The third of Gresley’s GNR Pacifics did not emerge from Doncaster until after the 1923 Grouping, and became a member of the LNER’s A1 class. Although the LNER haphazardly started naming the Pacifics, it was the decision to exhibit No. 4472 at the British Empire Exhibition in 1924 that led to it being named and the name chosen was Flying Scotsman, the name by which the 10am departure from King’s Cross to Edinburgh was unofficially known.

- Class 7 4-6-2

- Built Doncaster 1923

- Owned by National Railway Museum

The engine’s next claim to fame was being chosen to head the first nonstop run of the ‘Flying Scotsman’ from King’s Cross to Edinburgh in May 1928 and, of course, there has been confusion between the locomotive and the train ever since, the train having been officially designated in 1927.

Although never regarded as the best of the A1s, No. 4472 then received another great honour in 1934 when it became the first steam engine in Britain to be officially recorded as travelling at 100mph.

By then the A1 design had been enhanced as a result of the 1924 locomotive exchanges with the GWR and new Gresley Pacifics were being built as A3s, with the older ones being progressively rebuilt. Flying Scotsman was one of the last Gresley A1s to remain in its original condition.

Flying Scotsman was rebuilt to A3 specification in 1949 and became BR’s No. 60103; by now the A3s had been displaced by the streamlined A4 Pacifics and Peppercorn’s A1s were coming on stream.

Nevertheless, very late in its life, along with most A3s, No. 60103 was given the benefit of a double chimney, which transformed its performance, if only for the last few months of its working life.

It is hard to imagine a steam engine having a better pedigree than that of Flying Scotsman; yet it was not selected for official preservation by the British Transport Commission, largely as a result of having been substantially rebuilt from its original condition.

However, Retford businessman Alan Pegler, who had already purchased the Ffestiniog Railway, bought Flying Scotsman on withdrawal in January 1963, with the intention of keeping it running on the main line.

No. 60103 set off from King’s Cross on its last run in BR service, the 1pm to Leeds on January 14, 1963. It left the train at Doncaster, went into the works and emerged in April in Alan Pegler’s ownership, with single chimney reinstated and in LNER apple green livery carrying the number 4472.

And Pegler negotiated a contract with BR for its continued operation until 1972, a contract that no one else managed to obtain. No. 4472 gradually penetrated many unfamiliar parts of the BR system, this being made easier from 1966 after the purchase of a second tender.

From October 1967, Flying Scotsman became the only privately-owned steam engine able to run on BR and from August 1968 and the end of BR steam, it was Britain’s only main line steam engine. Yet, rather than capitalise on this monopoly situation, Pegler took his engine to the United States for a promotional tour. After a successful tour, another tour was embarked on that proved disastrous. Pegler went bankrupt, the engine was seized by creditors and the future looked bleak.

A rescue operation was masterminded by long-time Scotsman minder George Hinchcliffe, bankrolled by the Hon. William McAlpine. In the nick of time, No. 4472 was on a ship heading east across the Atlantic, arriving in Liverpool in February 1972. It was quickly overhauled at Derby works, spent a summer season on what was then the Torbay Steam Railway and in September 1973 it returned to the main line passenger business.

Sir William based Flying Scotsman at Steamtown Carnforth for most of the period of his ownership but he moved it to Marylebone in 1985 when BR agreed to the running of steam tours in the London area. In 1988/89 though, Flying Scotsman was running across Australia and continuing to break new records.

Privatisation of Britain’s railways in 1994 though saw pop impresario Pete Waterman get involved in the railway and railtour business and he acquired a half share in the owning company for Flying Scotsman set up by McAlpine. It was an uncertain time though and the new joint owners would not commit to the cost of a major overhaul until things settled down.

Instead, Flying Scotsman had a light overhaul and embarked on a programme of operation on heritage lines. Perhaps even more more shocking was the fact that it emerged from this overhaul in 1963 BR condition in Brunswick green livery with a double chimney and smoke deflectors, carrying the number 60103.

When it proved impossible to keep the increasingly unreliable engine going, it was sold to Oxfordshire entrepreneur Dr Tony Marchington, who bankrolled not just the most expensive overhaul of a British steam locomotive to date, but what amounted to a rebuild, which elevated it from a Class 7 to a Class 8. Dr Marchington’s plans for upmarket dining trains across Britain were progressively downsized, but after Flying Scotsman emerged from its overhaul still with double chimney and smoke deflectors but back in LNER apple green livery as No. 4472 in 1999, it performed like no Gresley A3 had ever performed before.

It just did not earn enough money though and while it was arguably turning out more power than the frames, cylinders and motion could handle, maintenance was being carried out on a shoestring. Dr Marchington died and Flying Scotsman Ltd was effectively insolvent. Once again the A3 had an uncertain future.

The National Railway Museum launched a campaign to purchase it and overhaul it. The first objective was achieved and the engine arrived at York in 2004, still certified for main line use. The second objective proved more problematical for the museum. The unreliable engine was quickly withdrawn and the overhaul started but it was to take 10 years and cost millions of pounds more than anticipated.

Nevertheless, when Flying Scotsman returned to steam in late 2015 and entered service in 2016, its fame and popularity had increased to unprecedented levels. It has reverted to being a BR 1963-era A3 with double chimney and numbered 60103, but it is a Class 7 again and will not be hauling the size of train that it regularly did in the Marchington days. Nevertheless, it has proved to be a very capable engine as it embarks on the latest era in its eventful life.

GWR Castle No. 5043 Earl of Mount Edgcumbe

Only one Great Western express steam engine is serviceable at present but it is a very capable representative of the railway and the class that were both synonymous with the best in British steam locomotive design throughout the ‘Big Four’ period.

The Castle was one of the best-known and most highly-regarded locomotive classes of the GWR. The first one, No. 4073 Caerphilly Castle, emerged from Swindon works in 1923, the first of a class that remained in production right up to 1950 and eventually numbered 170 locomotives.

The GWR’s newly-appointed chief mechanical engineer Charles Collett used his predecessor Churchward’s Star class four-cylindered 4-6-0 of 1906 as the basis for the new design. The boiler was larger, but lighter to keep within the stipulated axle load limit. It retained the standard GWR

long-travel valves and Belpaire firebox and looked attractive and well-proportioned.

- Class 7 4-6-0

- Built Swindon 1934

- Owned by Standard Gauge Steam Trust

The Castles were an immediate success, and when Caerphilly Castle was exhibited at the British Empire Exhibition at Wembley in 1924, alongside Nigel Gresley’s new LNER A1 Pacific No. 4472 Flying Scotsman, the GWR claimed that the Castle was Britain’s most powerful express locomotive.

In subsequent locomotive exchanges, the GWR locomotive won the battle in terms of speed, power and economy and this led to improvements being made to the LNER Pacific design.

The LMS was also impressed with the Castle, and asked to either buy some or borrow the drawings from Swindon to build its own but Swindon said “no”. The Castles achieved an enviable reputation for speed during the inter-war years on such trains as the then world’s fastest, ‘The Cheltenham Flyer’.

The later Castles were built with little change to their dimensions, but in 1946, Frederick Hawksworth, Collett’s successor, introduced a higher degree of superheat that resulted in increased economy and, from 1956, double chimneys were fitted by BR to some engines, combined with larger superheaters, and this significantly improved their performance still further.

The last three Castles were withdrawn from Gloucester in 1965. The last of all was No. 7029 Clun Castle in December 1965, which had worked BR’s last steam train out of Paddington on November 27, 1965 and had outlasted the others by six months. No. 7029 was preserved and has seen many years of active service since and is expected to emerge from overhaul at Tyseley in 2017.

In March 1936, No. 5043 Barbury Castle was outshopped from Swindon but in 1937, it was renamed Earl of Mount Edgcumbe after a GWR director and it gained a reputation for being an excellent performer, based for many years at Old Oak Common.

In May 1958 it was fitted with its double chimney and revised draughting arrangements, which much improved its efficiency. During this year it was recorded as reaching 98mph on the up ‘Bristolian’.

After withdrawal in 1963, No. 5043 was sold for scrap to Woodham’s scrapyard at Barry. In September 1973 though, 7029 Clun Castle Ltd purchased No. 5043. Many years later, Tyseley Locomotive Works, led by chief engineer Bob Meanley, had developed the skills to undertake massive restoration projects such as No. 5043, and the decision was finally made to restore the engine and major work commenced in 2000.

On October 3, 2008, Earl of Mount Edgcumbe returned to steam and moved under its own power again after almost 45 years, returning to the main line 13 days later. No. 5043 was the sixth Castle to return to main line service but none had quite the same pedigree as No. 5043 with its long association with Old Oak Common, ‘The Cheltenham Flyer’ and ‘The Bristolian’.

It was a double-chimneyed example and the value of this was quickly proved, with No. 5043 outperforming not just other Castles but bigger engines, both from the GWR and other railways. It did not just run on former GWR routes either but tackled the famous gradients in the north of England such as Shap and Ais Gill with ease, even reaching Scotland on one occasion.

It culminated in one memorable run when to celebrate 175 years of the GWR, on April 17, 2010, Earl of Mount Edgcumbe triumphantly headed both down and up ‘Bristolian’ trains nonstop between Paddington and Bristol Temple Meads, its timings comparing favourably with steam days, despite the overall 75mph speed limit that now applies.

LMS No. 46100 Royal Scot

Surprisingly, although the National Collection of preserved locomotives, ultimately inherited by the National Railway Museum, often featured the first of a particular class, Royal Scot, which was privately preserved, is the only ‘first of class’ currently registered for main line use.

The LMS was slow to react to the leaps forward in steam design, as seen on the GWR and LNER in their first years of existence, as the LMS motive power dept was in a rather disorganised state at first. Initially, the LMS persisted with the small engine policy inherited from the Midland, but Henry Fowler started thinking seriously about a compound Pacific in 1926.

However, for various reasons the LMS management decided to hire four-cylindered Castle 4-6-0 No. 5000 Launceston Castle from the GWR, tried it out for a month between Euston and Carlisle and asked Swindon if it could have the drawings.

- Class 7 4-6-0

- Built North British 1927

- Owned Royal Scot Locomotive & General Trust

The GWR declined but in view of its obvious success, the LMS encouraged Fowler to curb his ambitions slightly and think about a three-cylinder simple 4-6-0 instead.

The result was the Royal Scot. These engines were needed urgently and 50 were ordered from North British, which could deliver them within a year. The engines were designed jointly by North British and Derby works partly following a set of drawings of the Southern Railway’s four-cylindered Lord Nelson 4-6-0. Although Fowler took little part in the design, it inevitably followed Derby traditions and is recognisable as a typical Fowler engine, with a big parallel boiler, and a disproportionately small tender.

They went straight into service in 1927 on West Coast Main Line expresses and Derby built a further 20. Fortunately, they proved to be successful from the start, although with such an increase in power over their predecessors, this was perhaps inevitable.

They were initially named after British Army regiments or historic LNWR locomotives, although the latter fairly quickly received regimental names.

From late 1931, straight sided smoke deflectors were added, later replaced by deflectors with angled tops, but their reign on the top expresses was brief, as William Stanier replaced them with Pacifics in less than 10 years. Stanier later decided to replace the parallel boilers of the Royal Scots with his taper boiler, a preference inherited from his early career on the GWR and with the replacement of the Fowler tenders with Stanier ones, the ‘converted’ Royal Scots appear to owe more to Stanier’s design thinking than Fowlers. The mechanical dimensions and design though were unchanged.

Conversion started in 1943 and was completed by BR in 1955. Stanier did not initially fit smoke deflectors but a few received them in a particularly distinctive style in the last days of the LMS and BR soon completed the job. Although primarily WCML engines, once displaced by Stanier Pacifics, the class was used on Settle & Carlisle services, Liverpool to York and some other Midland main line trains including St Pancras – Manchester, but started to be phased out from around 1960, the last one being withdrawn in 1965 from Carlisle.

No. 6100 was the first of the class, built in 1927 by North British in Glasgow and named Royal Scot starting a regimental naming policy for the class.

But in 1933, No. 6100 permanently changed identities with No. 6152 The King’s Dragoon Guardsman. No. 6152 had been built at Derby in 1930, and this ‘new’ Royal Scot was sent to the Century of Progress Exposition of 1933 and toured Canada and the United States with a train of LMS coaches.

In 1950, No. 46100 became one of the later members of the class to be fitted with a taper boiler by BR, in accordance with the conversion programme initiated by Stanier, but in October 1962 it was an early withdrawal from service from Nottingham shed.

It was bought by Billy Butlin and after external restoration at Crewe Works to LMS maroon livery, No. 6100 was taken to Skegness and arrived for display at Butlins holiday camp at nearby Ingoldmells on a Pickfords low loader on July 18, 1963 piped in by pipers from the 1st Battalion, The Royal Scots.

A later change of policy by Butlins saw No. 6100 loaned to the Bressingham Steam Museum in Norfolk, where it arrived on March 17, 1971, being quickly returned to steam in 1972. It gave footplate rides at the museum until 1978 and was sold by Butlins to Bressingham in May 1989.

Eventually, plans were made for the engine to be overhauled at Bressingham with the aid of an HLF grant to run at the museum in summer and on the main line in winter.

On March 20, 2009, Royal Scot was back in steam and finally made its heritage era passenger hauling debut at the West Somerset Railway, followed by an appearance at the Betton Grange Group’s Steel, Steam & Stars gala on the Llangollen Railway in April.

It had been a long time coming but this was not to be Royal Scot’s finest hour after all. While controversy raged over whether it should carry non-authentic LMS livery, and if so should it have smoke deflectors or not, the engine was found to be seriously mechanically flawed, and Bressingham simply did not have the resources to put it right. After sale to Jeremy Hosking’s newly-formed Royal Scot & General Locomotive Trust in April 2009, it was moved to Pete Waterman’s LNWR Heritage workshops in Crewe, pending a decision on how to proceed.

That decision took a long time, but eventually the work to straighten and line up the frames and cylinders was completed and the engine hauled its first main line passenger train since 1962, from Crewe to Holyhead and back on February 6, 2016.

It quickly proved to be a strong performer and has seen action in all parts of the country, from London to Devon and Scotland.

LMS Royal Scot No. 46115 Scots Guardsman

Fortunately, two Royal Scots have survived but their stories are sadly similar in that both spent much of the first 40 years of their preservation careers as either static exhibits or worse still, stripped down with uncertain futures. However their fortunes have both picked up with No. 46115 Scots Guardsman finally becoming the main line star it deserves to be in 2008, and No. 46100 Royal Scot itself following in 2016.

No. 6115 was built by North British in 1927 and named Scots Guardsman in 1928 after the Scots Guards. It was one of the early class members to be fitted with a taper boiler, by the LMS in 1947, and was painted in LMS 1946-style black livery. Being the first of the rebuilt engines to receive smoke deflectors, it became the only one to run with them as an LMS engine.

The last of the class in service, withdrawn from Carlisle Kingmoor shed in 1965, it was purchased by Richard Bill and moved to the Keighley & Worth Valley Railway on August 11, 1966. Considered too big to be of use there, it was never steamed but moved on to the newly-established Dinting Railway Centre on May 28, 1969, where overhaul commenced. It was returned to steam in 1978 authentic in LMS black livery, as No. 6115 complete with smoke deflectors.

- Class 7 4-6-0

- Built North British 1927

- Owned by West Coast Railways

The main line beckoned and Scots Guardsman had a test run to Sheffield and back in September followed by a couple of runs to York. But apart from an appearance in steam at Liverpool Road station in Manchester in 1980 and steamings at Dinting, that was it.

BR’s inspection criteria on superheater flue tubes had been tightened up as a result of an incident at Didcot and it could no longer be certified without further major work. It was eventually moved to Tyseley on September 5, 1989 but this did not prove to be the answer to the engine’s problems. The death of its owner saw it being offered for sale by his son and daughter and it was purchased initially by a trust involving Ian Storey and Mel Chamberlin for £1. However, a rift quickly emerged between various trustees and no progress was made until it was resold to the Waterman Railway Heritage Trust in April 2002.

Still nothing happened until yet another sale, this time to David Smith’s West Coast Railways of Carnforth.

In 2008 it was restored to main line standard, but now in BR green livery as No. 46115 and hauled its first railtour for no less than 30 years, on August 16, 2008 over the Settle & Carlisle line. Since then it has been in regular front line service and has turned in some good performances, particularly on challenging routes in the north of England, although it has suffered some bad luck necessitating major repairs on a couple of occasions.

LMS Princess Royal No. 6201 Princess Elizabeth

Remarkably, Princess Elizabeth is the only active main line express engine carrying pre-Nationalisation livery at the present time.

When William Stanier arrived on the LMS from Swindon where he had worked under Collett, he soon realised he could improve on Fowler’s Royal Scot 4-6-0s for WCML services and that a Pacific, a wheel arrangement already synonymous with the rival LNER’s ECML services, was the answer.

A prototype batch of three locomotives built in 1933, are often considered to be an elongated version of the GWR King 4-6-0, with four cylinders and a taper boiler. They were very long engines, initially running with ridiculously short Fowler tenders. Even the replacement Stanier tenders were still disproportionately short, but longer tenders would have meant many turntables having to be replaced.

- Class 8 4-6-2

- Built Crewe 1933

- Owned by Princess Elizabeth Locomotive Society

The first engines were No. 6200 The Princess Royal and No. 6201 Princess Elizabeth. The third prototype was constructed with the aid of the Swedish Ljungstrom turbine company and known as the Turbomotive, numbered 6202, but not named.

Eleven more standard Princess Royals were constructed after the first batch, all named after Princesses. Although Princess Elizabeth was to become HM The Queen, the first engine of a class that would haul the ‘Royal Scot’, was named The Princess Royal as Mary, Princess Royal was the Commander-in-Chief of the Royal Scots. However, the engines still became widely known as ‘Lizzies’. The design was quickly superseded by the more powerful Princess Coronation Pacific and no more ‘Lizzies’ were built.

The second Princess Royal, No. 6201, was completed in November 1933 at Crewe and named after the seven-year-old elder daughter of the Duke of York’s eldest daughter, Princess Elizabeth, who was to become HM Queen Elizabeth II.

No. 6201 was selected by the LMS to make a record breaking attempt in 1936; to run nonstop from Euston to Glasgow. The record was achieved and No. 6201 achieved lasting national and international acclaim, as did its driver, Tom Clark, of Crewe, who was awarded the OBE in recognition of his skills. Princess Elizabeth remains the locomotive that set the record for the longest, hardest and fastest nonstop run with a steam-hauled passenger train in Britain.

The Princess Royals were early withdrawals as dieselisation took hold and No. 46201 was put in store twice at Carlisle Kingmoor in 1961/2, but returned to service twice before final withdrawal in October 1962.

It was purchased by Roger Bell on behalf of the Princess Elizabeth Locomotive Society for £2160 and was moved on August 12, 1963 to the Dowty Railway Preservation Society at Ashchurch in Gloucestershire. In June 1965 it became the first LMS Pacific to be steamed in preservation by a very wide margin.

It did not make it on to the main line though in the brief period in the mid-1960s when a handful of preserved GWR and LNER steam engines hauled occasional railtours, apart from making a couple of light engine runs from Ashchurch. It finally took its place at the head of a main line railtour on April 12, 1976 and at this time its operational base moved to the Bulmers Railway Centre in Hereford. It had been no less than 12 years since an LMS Pacific had hauled a main line passenger train.

The Bulmers centre closed and Princess Elizabeth has led a nomadic existence, spending time based at several different heritage lines and centres, and undergoing a number of overhauls. On July 11, 2012 Princess Elizabeth hauled the Royal Train from Newport to Hereford and again from Worcester to Oxford as part of the Diamond Jubilee Tour. It is believed that it was the first time that HM the Queen travelled behind the locomotive that was named after her.

No. 6201 was withdrawn for overhaul at the end of December 2012 with the work being undertaken this time at Tyseley with a return to the main line in the summer of 2016.

The only active maroon steam engine on the main line and with a loud Stanier bark from its single chimney, ‘Lizzie’ has been a firm favourite with enthusiasts since its main line debut 40 years ago.

LNER A4 No. 60009 Union of South Africa

Union of South Africa is the only working main line certified steam engine in individual ownership, having been purchased by present owner, Scottish farmer and businessman John Cameron, on withdrawal by BR in 1966.

Sir Nigel Gresley’s A4 Pacifics became legendary as soon as the first one emerged from The Plant at Doncaster.

No. 2509 was named Silver Link; it was streamlined and carried a two-tone silver grey livery. Nothing like it had ever been seen in Britain.

- Class 8 4-6-2

- Built Doncaster 1937

- Owned by John Cameron

Its appearance alone captured the public imagination like no other steam engine but when it hauled the press run of the LNER’s new high-speed ‘Silver Jubilee’ King’s Cross – Newcastle express, and touched 112mph in the process, it set a new steam speed record.

The A4 was the natural development of Gresley’s A3 Pacific. A total of 35 A4s were built between 1935 and 1938, carrying a variety of names, many of which changed during their service lives. Liveries also changed; four were silver, many garter blue and a few standard apple green, although garter blue quickly became standard.

They got faster and faster; Stanier’s competition with his streamlined Princess Coronation Pacifics on the LMS encouraging Gresley to go faster still until on July 3, 1938, No. 4468 Mallard touched 126mph on Stoke bank, a record that stands to this day.

The heyday of the LNER A4s was very short though, as the Second World War saw them painted black and hauling a size of train they were never designed for. From 1945 they regained their status as Britain’s top express steam engines, with No. 60007 Sir Nigel Gresley holding the postwar steam speed record, of 112mph, also on Stoke bank.

The Deltic diesels very quickly displaced them from top-link ECML duties from 1961 and the A4s could easily have disappeared by 1964. Fate intervened though in the shape of BR’s disastrous decision to use North British-built type 2 diesels on Scottish Region expresses, a duty they were simply not capable of. The ScR A4s based in Edinburgh were increasingly hauling expresses to Aberdeen; the ER no longer needed its A4s and many moved to Scotland where they were extensively used not on Edinburgh – Aberdeen expresses but Glasgow – Aberdeen, essentially an LMS route, most engines being based at Aberdeen’s Ferryhill shed.

No. 4488 was built for the LNER in 1937. Although it had been allocated the name Osprey on April 17, 1937, when it came out of the paint shop at Doncaster on June 29, it had been renamed after the then newly formed Union of South Africa.

The five A4s with ‘Commonwealth’ names and a modified garter blue livery with stainless steel embellishments were allocated to the LNER streamlined expresses.

Union of South Africa went to Haymarket shed in Edinburgh from new and remained at that shed, fitted with a corridor tender and paying regular visits to King’s Cross on the non-stop expresses until the diesels took over the top ECML services.

No. 4488 lost its streamlined valances over the wheels during the war in 1942. In BR days, now numbered 60009, it belatedly had a double chimney fitted in 1958. In 1962 it finally left Haymarket for Ferryhill shed in Aberdeen where it became one of the A4s that worked the three-hour expresses to Glasgow.

Overhauls still took place at Doncaster though and it was the last BR steam locomotive to be overhauled there. In recognition of this, on October 24, 1964 it hauled BR’s last steam-hauled train from King’s Cross, 18 months after the terminus last saw regular steam services. It was withdrawn on June 1, 1966, shortly before the very end of the A4s.

Purchased by John Cameron in July, No. 60009 was moved by road in 1967 to work on Cameron’s Lochty Private Railway in Fife. But changed circumstances saw the possibility of a return to main line use and in 1973 No. 60009 moved to Kirkcaldy to be prepared for railtour use.

At first BR would only permit running from Inverkeithing, north of the Forth Bridge, to Dundee, but this was gradually extended to cover Edinburgh, Perth and Aberdeen.

For many years the only preserved LNER steam engine to carry BR livery, No. 60009 attracted a unique following among steam enthusiasts north and south of the border on its occasional outings to recapture its former glories on the Aberdeen road. It even broke new ground for the class by working over the Highland main line in 1980.

It wasn’t until 1984 when it finally ventured south of the border, to work a number of trains over the Settle & Carlisle line. In February 1989, No. 60009 arrived for overhaul at Bridgnorth on the Severn Valley Railway, returning to steam in January 1990 and even working on the line occasionally.

It returned to Scotland though and continued in main line operation, mainly north of the border. In May 1994 the locomotive left its Markinch base for the last time on a low loader bound for a working life mainly south of the border.

Its operating base in England has varied and it has been seen all over the UK on main line tours and occasional visits to heritage lines. It has since accumulated the highest mileage of any locomotive in the class, and a highlight of its career was in October 1994 when it hauled the first steam-hauled passenger train out of King’s Cross since 1969, commemorating the 30th anniversary of hauling BR’s last steam train from the terminus. This event had been made possible by Privatisation and Railtrack’s open access policy.

Union of South Africa arrived at Pete Waterman’s LNWR workshops at Crewe for an extensive overhaul. It returned to steam in mid-2012 and the highlight of the current seven-year stint on the main line came on September 9, 2015, when No. 60009 headed the official reopening train on the rebuilt Borders Railway, from Edinburgh to Tweedbank, conveying HM the Queen and HRH the Duke of Edinburgh.

LMS Princess Coronation No. 46233 Duchess of Sutherland

The Princess Coronations were the most powerful express steam locomotives ever to be built for the British railway network, estimated to be able to produce 3300 horsepower and with evidence to prove this was the case in practice.

It was much more than just an enlarged version of the Princess Royal and was to become arguably Britain’s premier express steam locomotive design and a firm favourite with enthusiasts right up to the present day.

The first five, Nos. 6220–6224, were built in Crewe in 1937; streamlined and painted blue with silver horizontal lines to match the new LMS ‘Coronation Scot’ train. The chief draughtsman at Derby, Tom Coleman, was responsible for most of the detailed design including the streamlined casing, in Stanier’s absence. In fact Stanier had doubts about its value. It was not even attractive in itself, but the overall effect in the livery chosen, was certainly worthwhile in publicity terms.

Prior to the introduction of the ‘Coronation Scot’, on trials just south of Crewe, No. 6220 Coronation achieved a speed of 114mph, beating the LNER’s A4 Pacific No. 2509 Silver Link’s 112mph, but entering Crewe station at a dangerously high speed and with passengers on board. This briefly gave the LMS the world steam speed record.

The second five, Nos. 6225–6229, were also streamlined, but were painted in traditional crimson lake, with gilt lining, but the next batch were not streamlined. In the end 38 were eventually built, 24 streamlined and 14 non-streamlined, the last two to a modified design, with roller bearings by George Ivatt, the last one, No. 46257 City of Salford by BR in 1948.

Nos. 6220–6234 had single chimneys when built but from No. 6235 onwards, they were built with double chimneys, and the older engines receiving double chimneys between 1939 and 1944. Smoke deflectors were fitted to the non-streamlined engines from 1945, but in any case, the streamlining was removed from 1946 onwards. Only three locomotives were still streamlined by Nationalisation and these were treated by 1949.

- Class 8 4-6-2

- Built Crewe 1938

- Owned by Margaret Rose Locomotive Trust

The class was a great success but inevitably dieselisation, and electrification of the WCML saw them lose their Top Link workings early in the 1960s with relegation to secondary duties, and after a few withdrawals, the remaining class members were withdrawn in one fell swoop in September 1964. We are lucky that although No. 46235 City of Birmingham was officially preserved, though never steamed again, two more were saved by Billy Butlin. It was a long time before either returned to the main line, but without him we may never have seen one of Britain’s premier express engines at work again after 1964.

No. 6233 entered traffic on July 18, 1938, the fourth of the first batch of five non-streamlined class members to be completed. In 1943, the engine was fitted with a double chimney and in August 1946 received smoke deflectors.

Allocated to Crewe North for much of its working life, the engine was withdrawn in early February, 1964 from Edge Hill shed in Liverpool4. Along with No. 46229 withdrawn at the same time, No. 46233 was purchased by Butlins and externally restored to LMS condition at Crewe and put on show at Butlins’ Heads of Ayr holiday camp in October 1964.

Along with No. 6100 Royal Scot from Skegness, No. 6233 was loaned to Bressingham museum in 1971 and was returned to steam in May 1974 but only for short distance footplate rides. In 1989, No. 6233 was purchased from Butlins by Bressingham.

A move to the Midland Railway – Butterley to join ex-Butlins Pwllheli Princess Royal Pacific No. 46203 Princess Margaret Rose on February 4, 1996 signalled a big change in the engine’s fortunes. The locomotive was acquired by Brell Ewart’s Princess Royal Class Locomotive Trust and restored in LMS 1946 condition in crimson lake livery with a double chimney and smoke deflectors, returning to steam on March 20, 2001. Its main line debut was a Derby – Sheffield test run on July 18 that year.

Sutherland had a hard act to follow in that the NRM’s No. 46229 Duchess of Hamilton had returned to the main line in May 1980 and worked regularly until 1998, breaking records as a matter of course.

No. 6233 made history on July 11, 2002 by becoming the first steam locomotive to haul the Royal Train on the main line, as part of HM The Queen’s Golden Jubilee celebrations. The train ran on the North Wales Coast line between Holyhead and Crewe conveying The Queen and the Duke of Edinburgh. A further Royal Train duty in March 2005 saw HRH the Prince of Wales travelling on the footplate for part of the journey over the Settle & Carlisle line.

On September 10 2009, Sutherland took a 632 tonne train up Shap, topping the summit at 35.8mph, and beating the record set by No. 6234 Duchess of Abercorn in 1939 with a 20 coach train of 620 tons when the summit was passed at 30mph.

On completion of a heavy general overhaul commencing in the winter of 2010, Sutherland appeared as No. 46233 in BR Brunswick green livery. The engine continues to prove its capabilities, turning in performances to match any of its Class 8 competitors.

LNER A1 No. 60163 Tornado

Tornado is radically different to all the other engines in only having been completed in 2008; a brand-new steam engine for the 21st century. Edward Thompson rebuilt Gresley’s original GNR A1 Pacific No. 4470 Great Northern in 1945, keeping it as an A1, and he reclassified the remaining Gresley A1s which had not been rebuilt to A3 specification, as A10s.

Thompson’s successor, Arthur Peppercorn, redesigned Thompson’s not highly successful prototype A1, keeping the same basic dimensions and continued to build his new A1s, the first, No. 60114 WP Allen, emerging from Doncaster in BR days in 1948.

Thompson’s rebuilding of Gresley’s designs met with little approval but Peppercorn’s Pacifics which reverted to Gresley’s principles, but updated to suit very different circumstances, were potentially outstanding.

- Class 8 4-6-2

- Built Darlington 2008

- Owned by A1 Steam Locomotive Trust

Peppercorn’s A1 Pacifics were fast, powerful, and above all, far more economical to run and maintain than their Gresley predecessors, but they suffered from one major flaw, they were rough-riding and therefore unpopular with crews.

The last two A1s just outlasted the A3s and A4s in England, but while everyone seemed to want to preserve and own an A4, no one was interested in the A1s and Nos. 60124 Kenilworth and 60145 Saint Mungo went for scrap in 1966.

This made the A1 Pacific, the only class of Pacific which ran in BR service, to be rendered extinct.

It might seem an unlikely thing to do, but a group of enthusiasts came up with a plan to build a brand-new steam locomotive in the 1990s. Not a tank engine for branch line services but a Class 8 express Pacific, and the logical choice was the extinct LNER Peppercorn A1.

Arthur Peppercorn’s widow was honorary president of the A1 Steam Locomotive Trust, builder of Tornado. At the age of 92, she lit the first fire in Tornado’s firebox in January 2008, and was later on the footplate for Tornado’s inaugural steaming at Darlington works, stating “My husband would be proud”.

Fundraising from public subscriptions and business sponsorship was phenomenally successful and the frames were laid at Tyseley in 1995, with a transfer to premises at Darlington on September 25, 1997 where work continued. A new boiler was built by DB Meiningen in Germany.

The first runs of the completed engine were in September 2008 on the Great Central Railway and a light engine test run from York to Scarborough took place in November of that year. The loaded main line test run from York to Newcastle was followed by the first public run, on the same route in January 2009.

The rough-riding characteristics of Peppercorn’s A1 design had been eliminated by some tweaks to the design and although the postwar A1s lacked the grace and style of Gresley’s designs, it had much improved economy, reliability and ease of maintenance.

The new Tornado immediately showed that it could outperform an A4 any day. But then it was 70 years newer than the newest A4!

It carried the number of the next A1 in the numbering sequence, 60163, the 50th class member and the name, after the aircraft which helped win the Gulf War, was an inspired choice.

Naturally the media followed every move of the new engine and with Flying Scotsman still stripped for overhaul, Tornado immediately assumed the mantle of Britain’s most famous steam engine and large crowds thronged the lineside wherever it went.

Highlights of Tornado’s first months of operation included a Royal Train from Leeds to York in January, followed by a naming ceremony performed by HRH Prince Charles and the Duchess of Cornwall.

A run from King’s Cross to Edinburgh as part of the BBC’s Top Gear TV programme, saw the engine complete the journey in a net time comparable with the best from ‘real’ steam days, with Network Rail pulling out all the stops to provide the best possible path throughout.

SR rebuilt West Country No. 34046 Braunton

Oliver Bulleid worked with Nigel Gresley on the LNER and was involved in many of Gresley’s more unorthodox experiments on the development of steam traction as well as the introduction of the high-speed streamline trains. He was headhunted by the Southern Railway on the retirement of Richard Maunsell in 1937.

The SR had gone in for large scale third rail electrification and replacement of Urie’s King Arthur and Maunsell’s Lord Nelson 4-6-0s on front line express services had not been a priority. By the time Bulleid was able to devote his attention to a new express steam design, Britain was in the throes of the Second World War and Bulleid had to pretend his new Merchant Navy Pacific was a mixed traffic engine.

In fact, while it was unorthodox in design and appearance, it was potentially one of the finest express engines to be produced in Britain, its one concession to the label of ‘mixed traffic’ being its 6ft 2in driving wheels giving it more power on the rail from what proved to be probably the best-steaming boiler ever produced in this country. Bulleid adopted a three-cylinder layout, as used almost universally by Gresley on his larger engines.

- Class 7 4-6-2

- Built Brighton 1946

- Owned by Royal Scot Locomotive Trust

Thirty Merchant Navies were built and revolutionised the Bournemouth and Exeter lines as well as the Kent Coast boat trains and Bulleid then developed a lighter version with greatly increased route availability. These were more like mixed traffic engines, although the SR had comparatively little serious freight traffic anyway.

Similar in appearance to the ‘Merchants’, with air-smoothed (as opposed to streamlined) casings, boxpok wheels and chain-driven valve gear, with big ornate nameplates and a striking malachite green livery, the West Country and identical Battle of Britain Pacifics were just as obviously express engines as their larger counterparts were, though the light ones could go almost anywhere on the branch lines of the South West.

Bulleid even had a unique numbering system and when built in 1946, Battle of Britain Pacific Braunton carried the number 21C146; the ‘C’ referring to three driving axles. The Bulleid Pacifics became the last working pre-Nationalisation express engines in Britain, with the Merchant Navies being the last Class 8 Pacifics in service, and took charge of the Bournemouth, Weymouth and Salisbury expresses until electrification in July 1967. Many 100mph+ performances were recorded in the last few weeks of steam.

They were too unconventional for BR though and with the unorthodox features, particularly the chain-driven valve gear, proving insufficiently reliable, the Merchant Navies were all rebuilt to more conventional Pacifics in the 1950s, to a design by Ron Jarvis which closely followed the BR Standard range.

A start was made on rebuilding the light Pacifics but with the end of steam in sight, the programme was never completed and some original engines survived right to the end.

Many Bulleid Pacifics ended up at Barry scrapyard, and all those were purchased for preservation. Many have been returned to steam but have proved costly to maintain in service and only one is currently main line certified, No. 34046 Braunton, which had been rebuilt by BR in January 1959, but withdrawn in 1965 and sent to Barry scrapyard.

It was one of the later ones rescued from Barry, by then in deplorable condition, and moved to a proposed steam centre at Preston Park, Brighton in 1988. This project never got off the ground and Braunton continued to deteriorate until it was sold to the West Somerset Railway Association and moved to Minehead in January 1996.

The engine was subsequently resold and joined Jeremy Hosking’s fleet after which restoration finally started. No. 34046 first steamed in July 2007 and ran regularly in WSR service. Eventually it moved to Riley’s works at Bury for upgrading to main line condition and on July 16, 2013, it made its main line debut on a test run from Carnforth

During 2016, Braunton has been running as classmate No. 34052 Lord Dowding but will revert to its correct identity in the new year. It is currently the only Bulleid Pacific running on the main line, although there have been several others in past years, including two of the larger Merchant Navy Class 8s.

BR Standard Britannia No. 70013 Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell is generally regarded as having been BR’s last working standard gauge steam engine.

On the creation of the Railway Executive in 1947 in preparation for the Nationalisation of the railways in 1948, Robert Riddles was appointed member of the Railway Executive for mechanical and electrical engineering. He had worked with Stanier, Fairburn and Ivatt on the LMS and his principal assistants were also former LMS men.

In this post Riddles was responsible for the policy of continuing the construction of steam locomotives, on the basis that it was not worth changing to diesel traction when the ultimate aim was electrification.

Riddles was responsible for the initiation of the well-known ‘interchange trials’ of 1948 and envisaged that Britain’s railways would use electric traction in the long term, with steam traction in the intermediate.

With his team, he set about designing and building a set of 12 standard locomotive designs, usually referred to as the BR Standards. Officially these incorporated the best practices of all of the ‘Big Four’ railway companies, as theoretically established by the interchange trials.

Inevitably, LMS practices tended to predominate, and like Riddles’ wartime austerity designs, his BR Standards were also designed for simplicity, ease of maintenance, and the ability to burn poor quality coal. Although the BR Standards were generally a success, there has been criticism of the policy pursued by Riddles, as he could easily have simply continued building the best of the latest designs from each of the ‘Big Four’.

In fact at total of 999 of Riddles’ Standard designs were built by BR, and far more to other, pre-1948 designs.

It is quite possible that Riddles carried his enthusiasm for steam a bit too far, but he was a steam enthusiast, and no one gets into the position of CME – particularly of a newly-formed national railway company; almost certainly the last in a line of railway engineers from Stephenson through Webb, Churchward, Gresley and Stanier – without having a desire to design and build memorable steam engines.

Designed at Derby in 1951, the first BR Standard design to emerge was a Class 7 two-cylindered Pacific. No such thing had ever been seen in Britain before. There was little need for them except on the Great Eastern lines. A few went to the Western Region to supplement the Castles but the region generally hated them.

The choice of the name Britannia for No. 70000, the first of the new Pacifics, reflected the regard Riddles felt for the LNWR where he had started his railway career. Not only did it carry a name of impeccable LNWR pedigree but it was even painted black in accordance with Riddles’ preference, although this was quickly replaced by standard Brunswick green.

The Britannias had 6ft 2in driving wheels, following Bulleid’s Pacifics and Peppercorn’s LNER A2s, both of which had proved that this was no obstacle to high speed performance.

The Britannias revolutionised the GE main line, but only for 10 years, and once moved away from East Anglia, they moved around various sheds gradually becoming concentrated on the LMR, where they became the last working British Pacifics, but they had ridiculously short lives on the front line services they were designed for.

No. 70013 was named Oliver Cromwell and was one of many of the class allocated to the GE section for Liverpool Street – Norwich expresses. Along with all the GE-allocated engines it moved to the LMR in the early 1960s and the class gradually became concentrated at the Carlisle sheds.

When it emerged from Crewe works after a general overhaul in February 1967 carrying fully lined-out Brunswick green liver and even a nameplate (on one side), there was a small ceremony to mark the last steam overhaul to be carried out on a BR steam locomotive.

It returned to Carlisle for the rest of the year but actually spent most of its time in store in scruffy condition. It did get cleaned for one final duty in regular service, a football special on December 31, 1967 which it worked from Carlisle to Blackpool. The return saw a good performance up Shap from a standing start at Tebay, unbanked as the last bankers had been withdrawn.

It marked the end of steam at Carlisle and the withdrawal of all the other surviving Britannias. No. 70013 moved to Carnforth but not for regular use. Stored for much of the time under a tarpaulin it emerged only for occasional enthusiasts’ railtours in north-west England. The frequency of these increased between March and August 1968 as the end of BR steam approached.

The very last BR steam train was ‘1T57’, the ‘Fifteen Guinea Special’ of August 11, 1968. Oliver Cromwell worked the train from Manchester Victoria via Blackburn and Hellifield to Carlisle. Three LMS ‘Black Five’ 4-6-0s also played a part in hauling the train but as a named Class 7 Pacific, it was always considered to be Cromwell’s day.

Afterwards, No. 70013 ran light engine from Carlisle to Lostock Hall shed at Preston, then overnight to Norwich. It was placed on loan to the Bressingham Steam Museum, a decision which was later to cause some controversy. The class pioneer, No. 70000 Britannia had already been nominated for official preservation as part of the National Collection.

Cromwell continued with footplate rides at Bressingham for a while but never left there and never hauled another train… … until August 10, 2008, from Manchester Victoria to Carlisle, exactly 40 years on from its last appearance on the route, hauling BR’s last steam train.

After a false start 15 years earlier when even the ownership of the locomotive was called into question, agreement had finally been reached for No. 70013 to leave Bressingham to be overhauled on the Great Central Railway at Loughborough and returned to main line action. It was a close-run thing but Oliver Cromwell hauled the 40th anniversary ‘Fifteen Guinea Special’ as planned.

For a two-cylinder Class 7 with 6ft 2in driving wheels, No. 70013 has proved to be a powerful engine, holding its own against its bigger Class 8 cousins.

Advert

Enjoy more Heritage Railway reading in the four-weekly magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Enjoy more Heritage Railway reading in the four-weekly magazine. Click here to subscribe.